“But I will encamp at my temple to guard it against marauding forces. Never again will an oppressor overrun my people, for now I am keeping watch.” (Zechariah 9:8)

While preparing for a new neighborhood near the city of Modiin, Israeli archaeologists unearthed a farmstead dated to the Maccabees. Clues such as a silver coin cache also suggest the clan’s involvement in the AD 66 and AD 132 revolts against the Romans.

During the Late Hellenistic Period, the extensive hillside agricultural estate, which about midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, apparently served as home for an extended family who cultivated grain fields in the valleys, and vineyards and orchards in the hills. At the estate were found traces of an olive press, dozens of winepresses, and storehouses.

In addition, “numerous bronze coins minted by the Hasmonean kings were also discovered in the excavation. They bear the names of the kings such as Yehohanan, Judah, Jonathan or Mattathias and his title: High Priest and Head of the Council of the Jews.” (IAA)

According to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) excavation director Avraham Tendler, the estate house itself “was built of massive walls in order to provide security from the attacks of marauding bandits.”

The find also suggests that the estate was used as a stronghold during both Jewish revolts against the Romans — the First Jewish-Roman War of AD 66–73 and the Bar Kokhba Revolt of AD 132–136.

The Modiin excavation reveals that the Jews of Judea strengthened the estate walls prior to the Simon Bar Kokhba revolt in AD 132. To do that, the inhabitants “filled the living rooms next to the outer wall of the building with large stones, thus creating a fortified barrier.”

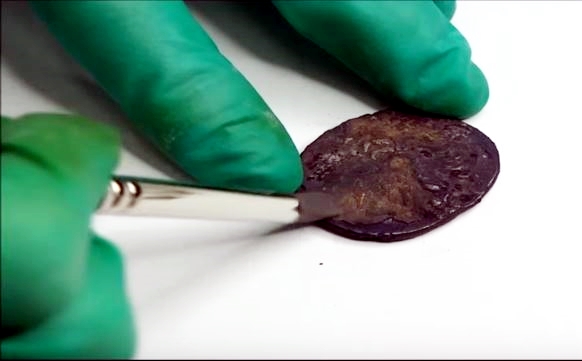

And at least two years after the Bar Kokhba Revolt had begun, one rock that pressed against a wall of the estate was used to hide away 16 precious silver coins, one or two from every year between 135–126 BC, representing nine consecutive years.

Some of the coins discovered are stamped with the date “Year Two” (of the revolt in 66) and the slogan ‘Freedom of Zion,’” according to an IAA press release.

This silver coin minted during the Bar Kokhba revolt reads “To the freedom of Jerusalem” on the obverse, which depicts trumpets, and “Year two of the freedom of Israel” on the reverse, which depicts a lyre.

Among the 16 silver shekels and half-shekels are coins bearing the faces of King Antiochus VII and his brother, Demetrius II.

“It seems that some thought went into collecting the coins, and it is possible that the person who buried the cache was a coin collector. He acted in just the same way as stamp and coin collectors manage collections today,” the IAA’s Coin Department head Dr. Donald Tzvi Ariel said.

Tendler has another theory. “The cache that we found is compelling evidence that one of the members of the estate, who had saved his income for months, needed to leave the house for some unknown reason. He buried his money in the hope of coming back and collecting it, but was apparently unfortunate and never returned,” he stated. “It is exciting to think that the coin hoard was waiting here 2,140 years until we exposed it.”

The archaeological survey of the farmstead has also revealed more secrets, including “hiding refuges that were hewn in the bedrock beneath the floors of the estate house.”

“These refuge complexes were connected by means of tunnels between water cisterns, storage pits and hidden rooms,” Tendler says. “In one of the adjacent excavation areas a miqwe [mikvah — a Jewish bath for ritual immersion] of impressive beauty was exposed; when we excavated deeper in the bath we discovered an opening inside it that led to an extensive hiding refuge in which numerous artifacts were found that date to the time of the Bar Kokhba uprising.”

The new neighborhood in the Modiin-Maccabim-Reut area will feature an archaeological park highlighting these finds, according to the IAA.