“Just then a woman who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years came up behind him and touched the edge of his cloak. She said to herself, ‘If I only touch his cloak, I will be healed.’” (Matthew 9:20–21)

For those Jews who wish to stay as close to the performance of God’s commandments as possible, you might say that Judaism is a “fringe” religion, with four tassels (tzitzit) hanging from the fringes of our clothes.

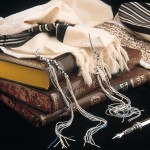

In Biblical times, in obedience to Numbers 15:38–41, men would attach the tassels to the four-cornered tallit (cloak or gown) that was customarily worn.

Originally, the tallit may have appeared as an outer garment bearing the fringes commanded by God. It probably resembled the abayah, the blanket worn by Bedouin to protect them from the elements, which has black stripes at the ends.

It was finer, however, and similar also to the pallium (rectangular cloak worn by Greek and Roman men).

“Speak to the children of Israel and say to them: They shall make for themselves fringes on the corners of their garments… And this shall be tzitzit for you, and when you see it, you will remember all the commandments of God, and perform them.” (Numbers 15:38–39)

After the Jewish People were exiled from Israel, their style of dress was influenced by their Gentile neighbors, and the tallit became a garment worn for prayer instead of a garment worn daily.

Still, in terms of dress, such assimilation has not completely overtaken the Jewish community.

Today, one of the things that distinguishes Orthodox Jews from the secular or more moderate is their “unusual” manner of dress.

“In the small Galilee town in which I lived for close to 20 years, an Orthodox group that followed the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, the Breslovim, slowly grew in numbers over the years and steadily outgrew the secular Zionists. What distinguished the two groups from each other was not only their orientation toward being Jewish but also the way that they dress,” said Barry, a Messianic Jew.

“The labor Zionists could be found walking the streets or riding their tractors to their fields dressed in typical work clothes, dark blue shirt and pants, and on their heads the Kova Tembel, the unique Israeli cloth or canvas hat with a broad rim to keep out the sun, worn by most farmers and field workers,” he continued.

“The Breslovim on the other hand, were dressed as if they had just walked out of an 18th century eastern European Jewish Shtetl, small village in which Jews congregated up until the Holocaust,” he said.

“Brezlovim are distinguished by their black hats and black suits and vests, which they wear even when the temperature reaches 120º F in the shade. And no matter what the weather, they wear the long-sleeved white shirt.

“Although you perhaps cannot see it, underneath their clothes is a poncho called the tallit katan with the tzitzit coming out from beneath the shirt,” he said.

Of course, other ultra-Orthodox also wear the tallit katan, and sometimes the tassels visibly dangle from under a regular button down shirt, sweater, and even a T-shirt.

The tzitzit of the tallit katans of two Jewish men are worn outside, while the third man has tucked in his tzitzit.

Wearing the Tallit

“Make tassels for yourselves on the four corners of the garment with which you cover yourself.” (Deuteronomy 22:12)

Today, there are two ways in which observant Jewish men and boys keep the commandment to wear tzitzit.

The first is to wear the tallit gadol. Worshipers wrap themselves in this large sheet-like prayer shawl during morning prayers. It is usually made of linen.

The second way is to wear the tallit katan, which takes the form of a small poncho and is worn under the shirt, often over an undergarment so as not to actually touch the skin.

From the corners of these garments hang the tassels called tzitzit.

They serve as a constant reminder of the 613 commandments of the Torah, the Five Books of Moses.

A Jewish father helps his son adjust his tallit gadol during the boy’s bar mitzvah at the Western (Wailing) Wall.

The wearing of tzitzit is only observed during daytime hours (with the exception of Yom Kippur [the Day of Atonement].

Because the Torah says, “And you will see [the tzitzit] and you will remember all the commandments of God,” it is believed that it is only proper to wear the tzitzit during the day, since they cannot be seen at night.

Therefore, nighttime clothing does not require tzitzit; although, we are not restricted from wearing them at night, and some even sleep with them.

The Kabbalah, a Jewish form of mystical teachings, describes the tallit as being a representation of God’s infinite transcendent light.

The fringes are seen as suggesting the Divine Light thought to permeate creation. It is believed that by wearing the tallit gadol or the tallit katan, a Jewish person synthesizes these two elements and they become real in his life. (Chabad)

A Jewish father pulls his sons (who are each wearing a tallit katan) under his tallit gadol during the Priestly Blessing at the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

A special prayer is said when putting on the tzitzit:

Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheynu Melech ha’olam asher kidshanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu al mitzvat tzitzit.

[Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us concerning the mitzvah of tzitzit.]

Those who wear the tallit while praying do not have to recite this prayer for the tzitzit since the prayer for wearing the tallit (general term for tallit gadol or large prayer shawl) covers the tzitzit as well.

Before the morning prayers, the tallit is put on before donning the tefillin (phylacteries).

When a man wraps the tallit around him, he says the following prayer:

Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheynu Melech ha’olam asher kidshanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hitatef b’tzitzit.

[Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us to enwrap ourselves with tzitzit.]

During two parts of the morning prayers, it is customary to hold the fringes of the tallit in the hands: during the Baruch She’amar and during the Shema. The prayer book instructs regarding the proper time to do this.

A Jewish artisan who weaves tallitot ties the tzitzit to the four corners of the garment. (Israel photo gallery by Noam Chen)

Tallit Regulations

Tallitot have no specific size requirement, although the Talmud does say the tallit should be large enough to cover “a small child able to walk.”

A tallit may be created from an assortment of materials such as wool, silk, or rayon.

A variety of decorations and artistic patterns adorn the tallit gadol, although they all have a band sewn across the top called the atarah (crown). This section may be decorated with silver squares or fancy embroidery. Most atarah also contain the blessing that is recited when putting on the tallit.

When one is called to the reading from the Torah, known as an aliyah or going up to the bimah, the platform from which the Torah is read, it is the custom to place a corner of the tallit on the first word to be read, and to then kiss the corner of the tallit that has touched the Torah scroll.

Because the tallit represents God’s commandments and the blessing for donning the tallit appears on atarah of the tallit, it is improper to wear the tallit into the bathroom since sacred writings cannot be brought into the bathroom.

In many synagogues, there is a tallit rack outside the bathroom.

Jewish men are traditionally buried wrapped in their tallit. When this is done, the atarah is removed and one of the fringes cut off. This renders the tallit invalid and symbolizes that the dead are no longer required to keep the commandments.

The black box of tefillin (which contains Scripture) and the tzitzit with the tekhelet (blue thread) of the tallit.

The Blue Thread

Among the tzitzit, the Torah commands the inclusion of a blue thread called the tekhelet.

This is dyed with a special dye that comes from the blood of a shellfish called chilazon, which is found only in the Mediterranean Sea.

When the Jews were scattered from Israel, they lost the use of this special thread for many centuries.

More recently, with the return of the Jews to Israel, some rabbis claim to have found this shellfish using its description in the Talmud, and now tallit can be found sporting the blue thread. Other rabbis say, however, that the thread will not reappear until the coming of the Messiah.

Do Women Wear Tallitot?

In general, women are exempted from wearing tzitziot (plural for tzitzit) and are discouraged from wearing either tzitziot or the larger tallit, although this is debated in the Talmud:

Menachot 43a: “The rabbis taught: all are obligated in the laws of tzitzit: priests, Levites, and Israelites, converts, women, and slaves.” However, “Rabbi Shimon exempts women because it is a positive commandment limited by time and from all positive commandments limited by time, women are exempt.” (Women of the Wall)

Many rabbis argue that this exemption underscores the fact that women have greater spiritual awareness and do not need tangible reminders to observe the mitzvot!

Still, this exemption has become a sore issue recently with the “Women at the Wall,” a multi-denominational group of women who struggle for equal rights of women to pray at the Western Wall.

As a group, they hold monthly meetings at the Western Wall on Rosh Chodesh, the first day of each new month of the Jewish calendar, in which they sing songs and read from the Torah.

They also wear religious garb including the tallit and tefillin (phylacteries) and the kippah or religious skullcap, all of which are usually worn exclusively by men and under the traditional rabbinic ruling described above.

Consequently, their presence at the Wall, although restricted to the Women’s section, has upset some members of the Orthodox Jewish community and actually led to protests and arrests of the women.

In May 2013, a judge ruled that a 2003 Israeli Supreme Court ruling that had prohibited women from carrying a Torah or wearing prayer shawls had been misinterpreted and that Women of the Wall prayer gatherings at the Wall should not be deemed illegal.

Board member Rachel Cohen Yeshurun (left) and former director Lesley Sachs, of the Women of the Wall, detained by police for wearing tallitot at the Kotel (Western Wall) in Jerusalem.

The movement among women to wear the tallit is not new and not limited to Israel.

“I first became aware of this trend among women to dress in religious garb and wear tefillin when in the early 1980s while living in Cincinnati Ohio I dropped by the Reform rabbinical seminary, the Hebrew Union College [HUC], to join in the customary mid-morning prayers,” Barry said.

“Twenty years earlier as a rabbinical student at HUC, I had regularly attended these mid-morning prayer sessions which were more or less required as a part of the curriculum,” he said. “I was at first surprised to see that what had once appeared to be an almost church-like chapel complete with wooden pews and an organ was now bereft of any furniture, but the cold wooden floor was now covered with a thick rug.

“Instead of the closely packed sanctuary, I witnessed a handful of students, many of whom were women (women rabbinical students were first introduced in the mid-60s) praying in Hebrew the Shacharit (morning prayers).

“The amazing thing, at least to me, was that the male students wore no religious apparel while the female students were wrapped in the tallit gadol and wearing tefillin (phylacteries) and kippot. The male students looked completely secular while the female students looked like Orthodox Jews, but not Orthodox women, rather like Orthodox men.”

As the Reform movement became increasingly popular in Israel, and since a healthy percentage of Reform rabbis are women, both in Israel and in the US, this desire to wear traditional garments during worship, although not a Scriptural or rabbinic requirement, also spread to women members of the Conservative and even Orthodox (modern Orthodox) movements in Israel, resulting in the creation of Women at the Wall.

A poll reported in the Israeli newspaper HaAretz indicated that as many as half of the Israeli public support the efforts of this organization, and that men (51.5%) are more inclined to support the women’s prayer group than women (46%).

Nevertheless, although they have the support of large American non-Orthodox denominations, and the backing of the Israeli government, the Rabbi of the Western Wall, who is responsible for keeping order at the Wall, continues to view their presence as a provocation.

![Women of the Wall praying and reading Torah at their monthly Rosh Chodesh (new moon, literally head of the new [month]) service. Women of the Wall praying and reading Torah at their monthly Rosh Chodesh (new moon, literally head of the new [month]) service.](https://messianicbible.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/720-Women_Praying_at_Robinsons_Arch-by-Michal-Patelle-600x400.jpg)

Women of the Wall praying and reading Torah at their monthly Rosh Chodesh (new moon, literally head of the new [month]) service.

Persecution and Outward Symbols of Jewish Identity

Although Jews customarily wear the tzitzit as a sign of pride here in Israel, increasingly Jews in Europe fear being identified as Jews in public.

But as Islamic communities grow in size and anti-Israel feelings become increasing viral around the world, one might question the safety of wearing Jewish garb such as a kippah or tallit in public in traditionally hospitable nations.

Before European attacks on Jewish institutions in recent years, between one-fifth and one-third of Jews living in Europe reported being afraid to wear even a kippah in public, let alone the tallit. Now it is probably closer to 100 percent.

Moreover, at Jewish houses of worship and other establishments worldwide, there is an increased necessity for armed guards to protect Jewish worshipers and the buildings themselves.

Such fear prompts Israeli leaders to call on the Jews of Europe to immigrate to the safety of Israel.

As we continue to bring the Good News of Yeshua to the Jewish People in Israel and the world, please join with us as we plant seeds and reap a harvest during these troubled last days. We cannot do this vital work without your help.

“The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into His harvest field.” (Luke 10:2)