“I will keep you and will make you to be a covenant for the people, to restore the land and to reassign its desolate inheritances, to say to the captives, ‘Come out,’ and to those in darkness, ‘Be free!’” (Isaiah 49:8–9)

In 1939, just before World War II broke out, 669 children, mostly Jews, stood on the platform of Prague’s Wilson Railway Station making farewells to parents and siblings, many of whom would die during the Holocaust in Nazi death camps.

Some pleaded with their parents to not send them away.

“I was begging them to take me home,” Czech physician Renata Laxova recalls. “I was promising to always eat spinach. I had always refused, which had been a significant issue in our home. My parents told me the truth. They said, ‘We are sending you away. There is nothing more we want than to have you with us. But we want you to learn in school and be safe. We will do what we can to follow you. If we can’t follow you, we will come and get you when this occupation is over.'” (Detroit Free Press)

The children’s escape from certain death in Hitler’s ovens was orchestrated by an unknown hero, a 29-year-old London stockbroker named Nicholas Winton.

“He rescued the greater part of the Jewish children of my generation in Czechoslovakia,” said Vera Gissing, the author of the memoir Pearls of Childhood. “Very few of us met our parents again: they perished in concentration camps. Had we not been spirited away, we would have been murdered alongside them.”

For 50 years, his remarkable achievement went unrecognized.

In fact, many of Winton’s children would not have known who saved their lives had it not been for a serendipitous “accident.”

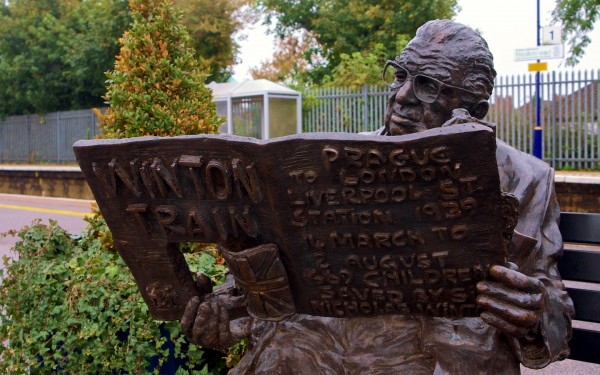

This sculpture on platform three of the Maidenhead train station by Lydia Karpinska depicts Sir Nicholas relaxing on a park bench, reading a book that contains images of the children he saved and the trains used to evacuate them. (Photo by Porsupah Ree)

Sir Nicholas Winton: Defender of the Weak

“Defend the weak and the fatherless; uphold the cause of the poor and the oppressed. Rescue the weak and the needy; deliver them from the hand of the wicked.” (Psalm 82:3–4)

Winton arrived in Prague nearly nine months before the German invasion of Poland that began World War Two.

Prague was already flooded with more than 250,000 refugees from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland (the area of Czechoslovakia where primarily native German speakers lived).

Three months before, in October 1938, Germany had annexed the Sudetenland.

On November 9–10, Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), Nazi troops and supporters had violently attacked the German Jewish community—smashing and looting Jewish homes and businesses.

After Kristallnacht, until 1940, Britain moved to lessen its obstacles to immigration, permitting entry to an unlimited number of Jewish children under the age of 17 from Germany and the German-held areas of Austria and Czechoslovakia. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Refugee-aid groups such as the British Committee for the Jews of Germany and the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany organized Britain’s Kindertransport (Children’s Transport) rescue efforts.

Broken glass littered the streets after Jewish-owned stores, buildings, and synagogues had their windows smashed on Kristallnacht, the beginning of Nazi Germany’s Final Solution.

Winton had not planned on going to Prague in December 1938. He had planned to go skiing in Switzerland.

On an impulse, he answered the request of his friend Martin Blake and went to Prague instead. Blake introduced his young friend to the organizers of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia.

Winton discovered the refugee camps in Prague were poorly equipped to protect against the cold winter and that the children of the refugees were all but forgotten.

But Winton had Jewish relatives who had escaped Germany. He had read Hitler’s Mein Kampf (My Struggle). He understood the implications of Kristallnacht and, hearing the glass breaking in his generation, could not ignore the evil.

He stepped into a river of Jewish refugees and began to divert a trickle of children away from the coming war with Nazi Germany.

His efforts over the next nine months were that of a hero in the making and are evidence of what one person can do even in “the shadow of the valley of death.”

He did not listen to the naysayers who said it couldn’t be done.

“Everybody in Prague said, ‘Look, there is no organization in Prague to deal with refugee children, nobody will let the children go on their own, but if you want to have a go, have a go.’ And I think there is nothing that can’t be done if it is fundamentally reasonable,” said Winton. (Power of Good)

Nicholas Winton: The Ingenuity of Britain’s Schindler

Winton used his two-weeks leave from work to set up a personal headquarters in Prague, at the Sroubek Hotel in Wenceslas Square. From there, he aimed to find a way to organize the evacuation of the refugee children into Britain.

From early morning to late into the night, “Britain’s Schindler” (to be named as such by former British Prime Minister Tony Blair) would meet with refugee parents to take the names, photos, and information of their children.

Winton would not have enough time in the day to meet them all, and he returned to England with about 6,000 names of children needing passage, leaving others in charge of duties in Prague. (L.A. Times)

However, when Winton returned to England, he found that organizations were helping thousands of children leave Germany and Austria, but no one was helping to bring children out of Czechoslovakia and into Britain. (Haaretz)

According to 60 Minutes, Winton sought to convince government officials to take him seriously “by taking stationery from an established refugee organization, adding ‘Children’s Section,’ and making himself chairman.”

“It just required a printing press to get the notepaper printed” and not a great amount of ingenuity, said Winton, who typed his requests for the children’s transportation under the header of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia.

Grand Hotel Europa (Sroubek Hotel) in Prague where Nicholas Winton began making arrangements to bring children out of Czechoslovakia into Britain.

Winton reached out to both English and American officials, even writing to President Roosevelt to have the United States take in the refugee children; however, Winton only heard back from a low-ranking official at the U.S. Embassy in London, who wrote: “The United States Government is unable.”

“The Americans wouldn’t take any, which was a pity; we could have got a lot more out,” Winton said.

England was willing to take Czechoslovakia’s children if Winton could find families to foster the children, and if he could provide 50 pounds per child to cover the cost of eventual return tickets back home.

To begin meeting these requirements, Winton linked up with the Refugee Children’s Movement organization upon his return to London, drawing from their knowledge in finding housing and money for refugees.

Winton’s mother, Barbara (nee Wertheimer), born in Nuremberg, Germany, and widowed as recently as July 1937, also signed on to the children’s cause. She and her husband, Rudolph Wertheim, had been Jews of Anglo-Bavarian descent before claiming to become Christian and changing their name to Winton in order to better assimilate into British life.

Barbara Winton took charge of the Children’s Section office and its volunteers, while Winton worked in the stock market by day and in the evenings “wrestled with the British bureaucracy” to push through travel documents for the children.

The Wintons advertised headshots of the children in need of shelter in the British press; from there, British families would choose which child they would like to care for, and the Wintons would arrange travel papers. (CBS)

“They will feed beside the roads and find pasture on every barren hill. They will neither hunger nor thirst, nor will the desert heat or the sun beat down on them. He who has compassion on them will guide them and lead them beside springs of water.” (Isaiah 49:9–10)

One of Winton’s Children was renowned CBC news correspondent Joe Schlesinger. In the above photo, he accepts a Canadian Journalism Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award. (YouTube capture)

For Winton, the urgency of the children’s circumstances would outweigh the responsibility of waiting for slow-moving bureaucrats to send travel documents.

The Children’s Section began to forge papers and pay Nazi officials to make sure the trains passed through Germany unobstructed. “It worked—that’s the main thing,” Winton told 60 Minutes.

After two months of planning, the Children’s Section successfully saw 15 children from Prague fly through Sweden to England on March 14, 1939.

The very next day, the first Nazi poster hung in Prague, stating (in its English translation), “By order of the Fuhrer and Supreme Commander of the German Wehrmacht. I have taken over, as of today, the executive power in the Land of Bohemia. Headquarters, Prague, 15 March 1939. Commander, 3rd Army, Blaskowitz, General of Infantry.”

Then, Adolph Hitler entered Czechoslovakia and its Prague Castle complex on March 16. Where previously the Prague Castle housed Czechoslovakia’s presidents, the kings of Bohemia and the emperors of the Roman Empire, Hitler declared the establishment of the ethnic-Czech Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, under Nazi rule.

With air travel no longer an option, Winton would organize nine groups of children to depart Czechoslovakia by train through the summer.

Even as violence against Jews, property confiscations, and forced labor spread throughout Czechoslovakia, the Nazis kept allowing Winton’s trains to leave, being that they fulfilled the policy of cleansing Europe of Jews. Safe-passage bribes ensured a successful transport. (60 Minutes)

On September 1, 2009, the 70th anniversary of the last Kindertransport, a special commemorative “Winton Train” set off from the Prague Main railway station. On the train, which headed to London via the original Kindertransport route, were several surviving “Winton children” and their descendants, who were welcomed by Nicholas Winton in London.

Winton’s trains would take the young refugees through Nazi Germany and into Holland, from there they would cross into England by ferry and finally travel to London. Many expected to see their parents after a few weeks or months, not knowing that they were to lose their families to war and genocide.

Winton recalled standing at Liverpool Street Station, watching the children arrive from afar.

“Inside I was cheering like a football match, but outwardly I was calm and quiet,” Winton said. “I knew that for every Jewish child safely deposited on the platform that day, there were hundreds more still trapped in Czechoslovakia. And I knew that because I was organizing this emigration entirely on my own, I wouldn’t be able to bring out a fraction of those in such terrible danger.” (Spartacus Educational)

Eight of the trains successfully made it out of Nazi territories, while the final and largest group of 250 children, scheduled for travel September 1, 1939, never made it to its destination. The Germans had invaded Poland and on September 3, Britain and France had joined the war. In retaliation, Germany blocked the ninth train. (Spartacus)

“None of the 250 children on board was seen again. We had 250 families waiting at Liverpool Street that day in vain. If the train had been a day earlier, it would have come through. Not a single one of those children was heard of again,” Winton said.

Nicholas Winton: Humble Hero

“Good deeds are obvious, and even those that are not obvious cannot remain hidden forever.” (1 Timothy 5:25)

Winton, who died July 1, 2015 at age 106, did not see the actions of his young adulthood as extraordinary. He saw this nine-month season of salvation as a “small event” that did not require heroism or much ingenuity. (Jewish Virtual Library)

“I work on the motto that if something’s not impossible, there must be a way of doing it,” Winton said.

“Winton knew how to correctly read the harsh reality,” said Avner Shalev, chairman of Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial, on July 2, 2015. Shalev noted that Winton “chose to leave his comfortable life and follow the voice of his conscience.” (Haaretz)

According to 60 Minutes‘ “Saving the Children,” which first aired on April 27, 2014, Winton recognized that “the people that I met couldn’t get out, and they were looking [for] ways of at least getting their children out.”

Sir Nicholas Winton meets with Czech students during a 2007 visit to Prague. (Photo by Hynek Moravec)

Of the 9,000–10,000 children rescued (mostly from Germany and Austria) through these transports to England, 7,500 were Jews. Of those, the London-born stockbroker would be responsible for the salvation of 669 children and more than 6,000 souls, which includes the refugees’ children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Few knew about Winton’s past life as a hero until almost 50 years later when his wife, Greta, found in the attic a scrapbook with Winton’s list of children’s names, their photographs, and letters from some of their parents.

She was amazed that he had never spoken a word about it and asked him to explain. He dismissed it, thinking that no one would be interested so many years later.

Greta passed on the information to a Holocaust historian, and later that year, the BBC brought Winton onto their show That’s Life to meet about two dozen of the children and their descendants that he had rescued. Winton did not know that they sat around him in the audience.

Show host Esther Rantzen directed Winton’s attention to this crowd behind him and said, “On behalf of all of them, thank you very much indeed.”

“I suppose it was the most emotional moment of my life, suddenly being confronted with all these children. But they weren’t by any means children anymore,” Winton said.

In 1988, Winton was awarded membership to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire and knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2003 for services to humanity.

In 2007, the Czech Republic recognized him with the highest military decoration, the Cross of the 1st Class. The Czech government also nominated him for the 2008 Nobel Peace Prize.

In 2014, the Czech Republic awarded him the Order of the White Lion.

Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial awarded Winton the honor of the Righteous Gentile, but he would not receive this title because his parents were Jewish—they converted to Christianity before he was born in order to assimilate into Gentile British society.

For Winton, though, it did not matter that he himself was of Jewish ancestry or that the majority of the children he would rescue were Jewish. Winton’s concern was only for the young: “I didn’t bring out Jews. I brought out children.” (The Jewish Week)

Further, Winton did not hold to any particular creed except, he said, to the “common ethics of all religions—kindness, decency, love, respect and honour for others—and not worry about the aspects within religion that divide us.” (Telegraph)

Sir Nicholas Winton (right) receives the Order of the White Lion from Czech President Miloš Zeman (left) at Prague Castle in Prague, Republic, on October 28, 2014.

Nicholas Winton: A Model for Every Person

Winton was not finished trying to make a difference.

During World War II, Winton volunteered in an ambulance unit for the Red Cross at Dunkirk, then toured Europe with the Royal Air Force becoming Flight Lieutenant. Post-war, he worked with the United Nations International Refugee Organization.

He invested largely in humanitarian works after the war, helping the mentally handicapped and building a pair of homes for the elderly.

“One can only hope somehow or other, goodness, kindness, truth, honor will prevail,” Winton said in a 2007 speech in Prague, organized by former Czech President Václav Havel. “People will realize it’s not good enough just to say, ‘Today I have done no harm. I’ve been a good person,’ but should have been able to say, ‘I was given the opportunity today and I did do some good.'” (CNN)

A commemorative event in July 2015 to honor the memory of Sir Nicholas Winton on the first platform at the Prague Main Railway Station at the sculpture, which is dedicated to him. The sculpture, which was created by Flor Kent, was unveiled on September 1, 2009.

Winton’s efforts have not been forgotten by those saved, nor by the more than 6,000 descendants who are alive today. In May 2014, Winton’s 105th birthday party was celebrated at the Czech embassy in London. About 100 descendants of the children he rescued were there to wish him happy birthday.

In gratitude for the gift of life, Winton’s children have reunions.

“I admire him greatly,” Laxova said at a 2014 reunion. “He not only saved the lives of 669 children, he changed their thinking. He changed the hearts and minds of their descendants. I am very convinced. I believe there is not one of us who [doesn’t] want to do something good to change the world.” (Detroit Free Press)

After his death on July 1, Winton’s son Nick said that his father’s legacy “is about encouraging people to make a difference and not waiting for something to be done or waiting for someone else to do it. It’s what he tried to tell people in all his speeches and in the book written by my sister.” (Independent)

Like Winton, may each of us, hear the glass breaking in our generation and stand against the evil tide of hatred and anti-Semitism.

Although theEven as violence against Jews, property confiscations, and forced labor that began in the Sudetenland soon spread throughout Czechoslovakia, the Nazis kept allowing Winton’s trains to leave in keeping with, being that they fulfilled the policy of cleansing Europe of Jews. That plus safeSafe-passage bribes. ensured a successful transport. (60 Minutes)