“Then the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life [chai]; and the man became a living being [soul-nephesh].” (Genesis 2:7)

What better toast can one say when honoring time with friends and family than speaking life to them, for them, and over them. Life permeates Hebraic thought and culture because it permeates the Word of God (YHVH).

From the moment God breathed chai (life) into Adam until the moment He speaks L’Chaim over the Bride at His Messianic Banquet, life is meant to be celebrated, protected, and honored.

Let’s see the ways that we can bring life into our homes and communities during our time on earth as we look forward to our eternal home with the Giver of Life.

Until 120!

Birthday cards in Israel often bear the message Until 120! (In Hebrew, Ad 120!), a reference to Moses who died at age 120, at which time “his eye had not dimmed, and his vigor had not diminished.” (Deuteronomy 34:7)

Physical and mental vibrancy up to age 120 is what Jews toast each other.

One hundred and twenty years is God’s normal lifespan for us, according to Genesis 6:3, and that is a good amount of time to produce significant good deeds, such as practicing the principle of pikuach nephesh (saving a life; literally, saving a living soul).

So significant is saving a life in Hebraic practice that it takes precedence even over the Biblical requirement to stop creating / working on Shabbat.

Why? Because saving a life is not forming, gathering, or separating as one does in creating something or doing “work.”

Saving lives restores people to God’s original design for His creation.

Wallah, a Gaza toddler who underwent emergency surgery at Israel’s Rambam Hospital for a massive tumor that was pressing on her brain, sits on her father’s lap as she talks to her Israeli doctor. (YouTube capture)

Yet, in Yeshua’s day, He received much condemnation from the Jewish leaders for healing the blind, lame, and possessed, even giving life itself back to the dead on Shabbat.

In doing these deeds, Yeshua revived the principle that preserving, restoring, and saving life is more sacred to God than anything because every person is created in the image of God (b’tzelem Elohim).

This is one reason the LORD has said, “You are not to stand idle when your neighbor’s life is at stake.” (Leviticus 19:16)

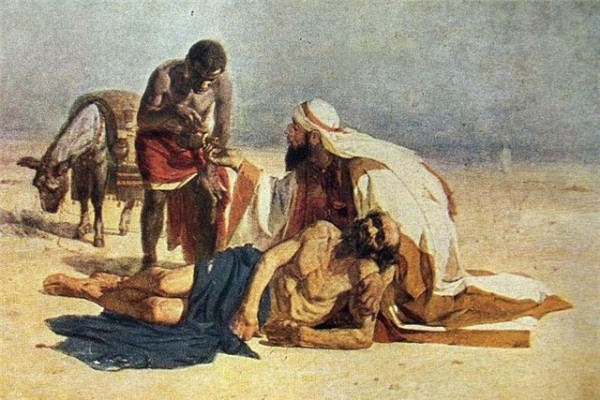

The Good Samaritan (1874), by Vasily Surikov depicts a Samaritan man helping to restore life to a stranger traveling from Jerusalem, who was beaten, robbed, and left for dead by the side of the road. Inspired by the parable of Yeshua (Jesus), it tells us that we are to help anyone in need of restoration. (See Luke 10:25–37)

Rabbinic thought on Shabbat healing has changed since Yeshua’s time. So precious is restoring life in Judaism today that the Code of Jewish Law states that “the physician’s right to heal is a religious duty.”

Although employers in Israel may not require a Jewish person to work on Shabbat, emergency personnel do work. And they do things on this holy day that the average Jewish person does not do.

Doctors, for example, are permitted by Rabbinic rulings to ride elevators, drive, and answer the phone, just in case a patient needs assistance.

And wherever there is an established Jewish presence, there is also a volunteer organization that honors life even after death on any day of the week they are needed.

An armored ambulance serves the West Bank (East Jerusalem) community in Israel’s search and rescue unit called ZAKA (Zihuy Korbanot Ason—Disaster Victim Identification). It is comprised of over 1,500 volunteers, including Muslim, Druze, and Bedouin who serve their respective communities.

Chesed shel Emet

Life in Israel is valued after death under the Jewish principle of chesed shel emet, which literally means grace of truth but generally refers to the truest act of lovingkindness. What makes their work so loving? The deceased cannot return their kindness.

In devastating terror attacks, for example, Israel’s ZAKA (Zihuy Korbanot Ason—Disaster Victim Identification) volunteer medics and servants, painstakingly search for and gather the bodily remains of all victims to make sure they receive a proper burial.

Even the body parts of suicide bombers are returned to their families.

We see the truest fulfillment of chesed shel emet—in fact the greatest love one can give another—when one lays down his life for a friend (John 15:3).

This same idea is found in the Talmud (Jewish Oral Laws), which states that “whosoever preserves a single soul…, Scripture ascribes [merit] to him as though he had preserved a complete world.” (Sanhedrin 37a)

No greater love has anyone exhibited than the One who freely gave all people of the world of any creed or color, a gift they can never repay—His very own life.

“For God so loved the world, that He gave His only Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have eternal life.” (John 3:16)

Tragically, not all people share the Hebraic value of life.

Terrorists enter restaurants, hotels, and bus stations, not to save lives, but to murder themselves, their sons and daughters, and fellow Muslims in order to kill as many Jews as possible.

Even in the midst of such tragedy, we see in Jewish communities that life prevails.

Medals of the 2009 Maccabiah Games (Jewish Olympics). In the middle is the Hebrew word חי—chai (life). Written above and below is the slogan Am Israel Chai (The People of Israel Live).

Am Israel Chai!

In Israel we sing with great gusto and confidence: Am Israel chai! (The People of Israel live!).

It is often a rallying cry of defiance, as it was on April 20, 1945, five days after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Lower Saxony, Germany.

On that Friday night, the Jewish Rabbi and Chaplain to the British Second Army, L.H. Hardman, held an Erev (Evening) Shabbat service for the survivors. A British attendee recalls the scene:

“Around us lay the corpses that there had not been time to clear away, even after five days. Forty thousand or more had been cleared, but there were still one or two thousand around, and people were still lying down and dying in broad daylight in front of our eyes. This was the background to this open-air Jewish service.

“During the service, the few hundred people gathered together were sobbing openly, with joy of their liberation and with sorrow of the memory of their parents and brothers and sisters that had been taken from them and gassed and burned.

“These people knew they were being recorded. They wanted the world to hear their voice. They made a tremendous effort, which quite exhausted them.”

After they finished singing Hatikvah, which would become Israel’s national anthem, Rabbi Hardman gave a shout:

“Am Israel Chai! The Children of Israel still liveth!” (BBC, YouTube)

Yes, there is grieving, there is mourning, and a coming together for shiva (literally seven), a customary period of seven days of family and friends sitting in unity and solidarity with loved ones.

But though “weeping endures for a night, joy comes in the morning.” (Psalm 30:5)

Jewish people grieve deeply and rejoice passionately. After shiva, dancing continues in synagogues, streets, and celebrations. It’s as if the spirit of His People still refuses to die.

As dancers leap and sing “Mashiach! Mashiach! Mashiach!” they seem to realize that Messiah is the One who gives us life, from eternity past to forever.

Toasting to Olam HaBah

When we toast L’Chaim, it could be said that we are actually speaking a blessing over two lives—the one we live on earth and the one to come.

In the Tanach (Hebrew Scriptures) and in Rabbinic Judaism exists the idea of olam (beyond the horizon) or l’olam va’ed (time spanning the ages and continuing into the future—beyond the horizon and further).

Many Rabbis teach that all Jewish People and all righteous Gentiles have a share in Olam HaBah, the World to Come. The quality of that share, according to Rabbinic thought, depends on the quality of mitzvot (good deeds) we perform in this life.

Though we will be rewarded in the world to come for our righteous deeds (Revelation 19:8), Scripture teaches that no Jew or Gentile is righteous enough on our own merit to enter the presence of God (Psalm 14:1, 143:2; Ezekiel 3:20; Romans 3:10).

That inherent right to eternal life was taken away from us shortly after God created the first man and woman.

This woman chose to follow a charming, divining creature of light (nachash in Hebrew), severring our relationship with the Creator of Life and closing the door to our Olam Habah.

A stained glass by Charles Lorin depicting Adam and Eve being banished from the Garden of Eden (Gan Eden).

There are always consequences to sin, even death, but God has never wanted any of us to perish forever because of our own sin or our parents’ sin. He allowed the first man and woman to continue living even after their devastating sin, but under new rules and new conditions: hard work and painful childbirth.

We always have another chance to get back up, move forward, and rectify our past behavior. We may have to operate under new rules in this life, but the path to redeem our time and produce good fruit is still open to us.

Likewise, even though our first parents closed the door to our Olam Habah, God set up a new path to our eternal home.

The woman who brought death to our bodies and souls would become the “mother of life.” Her name would be Chava, a form of the word life (Genesis 3:20).

Through her seed, a man would arrive and strike down the charming deceiver of death. God told this creature:

“I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel.” (Genesis 3:15)

Moreover, this man would become an offering for our sin (Isaiah 53:10).

Who is this man? How would we know Him when He comes?

There is no one Scripture that answers this question, yet some passages tell us more than others, such as the entire chapter of Isaiah 53.

Throughout the Hebrew Scriptures, there are hundreds of allusions, shadows, types, and outright prophecies that form a distinct picture of a man who would rectify the sin of our parents and restore us back to life in the presence of God.

Several of those Scriptures are being carefully examined and will be thoughtfully presented in a Jewish context in our Messianic Prophecy Bible and commentary.

“How can they call on him to save them unless they believe in Him? And how can they believe in Him if they have never heard about Him? And how can they hear about Him unless someone tells them?” (Romans 10:14)