Things are not always what they seem.

That holds true for free vacations, expensive coffee, and how we understand the teachings of Yeshua (Jesus), like this one:

“Take My yoke upon you, and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy, and My burden is light.” (Matthew 11:29)

What is Yeshua saying?

Christian leaders traditionally teach that Yeshua wants us to throw off the “burdensome” yoke of the Torah (God’s instructions to Moses and Israel) as well as the traditions and Pharisaic laws that were being placed on them (Rabbinic burdens).

But is that what His disciples understood from this teaching? And how can their Hebraic perspective on the ancient yokes of Israel change our lives today?

What Is a Yoke?

A yoke (ol in Hebrew) is a wooden collar placed upon a beast of burden, such as a donkey, to turn a mill, pull a plow, or to perform other work.

A double yoke is used to harness a team of two donkeys or other animals to combine their strength and pulling power. However, the Torah forbids yoking two different animals together (Deuteronomy 22:10).

As you can imagine, the imagery of the yoke as a tool of both servitude and teamwork lends itself to vivid metaphors and parables throughout the Bible. This is especially true in the days of Yeshua, since Christian tradition says He constructed them as a carpenter, along with plows. (Dialogue with Trypho, Ch. 88)

Yokes of Servants and Kings

To truly understand what it means to take up Yeshua’s yoke, we need to look at the many ways that this metaphor has been used since the days of early Israel.

The yoke, for instance, has often illustrated servitude:

The yoke of Jacob and Esau: Isaac tells his son Esau that he will serve his younger brother Jacob, but one day he will break free from that yoke. (Genesis 27:40)

The yoke has also been a symbol of the authority of a ruler:

The yoke of a king’s tyranny: When King Solomon’s son Rehoboam took the throne, the people asked him to lighten the burden that his father had placed on the citizens of the kingdom. Rehoboam showed no mercy, declaring:

“Whereas my father laid on you a heavy yoke, I will add to your yoke. My father disciplined you with whips, but I will discipline you with scorpions.’” (1 Kings 12:11)

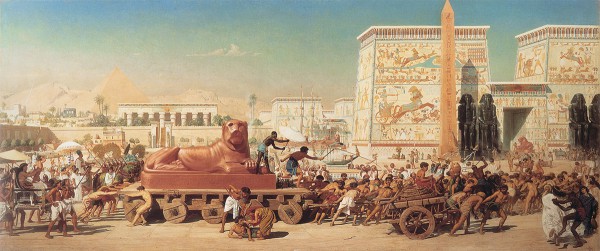

The yoke of a Pharaoh’s tyranny: God likened the enslavement of the Jewish People under Pharaoh to a yoke, saying to Israel, “Long ago I broke your yoke and burst your bonds; but you said, ‘I will not serve.’” (Jeremiah 2:20)

The yoke of Almighty God: The yoke is also a symbol of God’s holy rule. When God saved Israel out of Egypt, He yoked His People to Himself.

How? By giving them the Mosaic covenant, which detailed how to live holy, set apart lives—to become a miniscule copy of Himself. In that covenant, He also gave Israel promises of blessings for obedience and curses for disobedience (Deuteronomy 28–30).

The Lord said to the People, “Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls. But you said, ‘We will not walk in it.'” (Jeremiah 6:16)

Israel stood at the crossroads; prophets and priests alike cast off the yoke of God’s Torah, protection and favor. From the least to the greatest, all turned down the road of greed and deceit. (Jeremiah 6:13)

Moreover, the people stole and murdered, committed adultery and perjury, burned incense to Baal and followed other gods they did not know. (Jeremiah 7:9)

The consequence for that rebellion is just as applicable today as it was 2,700 years ago—if we are not yoked to God, then we are yoked to the enemy.

The yoke that Jeremiah wore: As a graphic and prophetic judgment on Israel’s rebellion, God told Jeremiah to “make yourself straps and yoke-bars, and put them on your neck.” (Jeremiah 27:2)

The yoke that Jeremiah wore was supposed to help prepare the People for the reality that one day soon all of Israel will have to “put its neck under the yoke of the king of Babylon.” (Jeremiah 27:2–8)

That graphic prophecy was fulfilled in 586 BC when King Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Jerusalem along with the Temple, and brought many of the Jewish People to Babylon under his rule.

The yoke that the people will want back: In spite of the rebellion, Jeremiah foresees a day when the People of Israel will tire of the yoke of exile and want to take back the goodness of the yoke of God.

“’There is hope for your future,’ says the LORD. ‘Your children will come again to their own land. I have heard Israel saying, ‘You disciplined me severely, like a calf that needs training for the yoke. Turn me again to you and restore me, for you alone are the LORD my God.’” (Jeremiah 31:17–18)

Jeremiah declares that a New Covenant will be enacted in which God’s yoke (His instructions) will be placed on the hearts of the People and the People will naturally know, desire, and do it. (Jeremiah 31:33–34)

The yoke of Roman tyranny: After the Jewish People returned from Babylon, they continuously lived under a foreign ruler’s yoke.

In the 1st century BC, Rome yoked Israel to itself, instituting heavy taxation and other regulations that placed great burdens on the Jewish People. In AD 68, a rebellion against Rome began in Judea. And in AD 70, the Romans took siege to Jerusalem and destroyed the Second Temple.

The Yoke of the Rabbis

By the time Yeshua was teaching people how to follow God, the other religious teachers of His day were adding rules and regulations beyond the Torah, making it difficult to follow God.

The Rabbis were “teaching as doctrines the commandments of men,” such as believing Yeshua should not heal on the Sabbath or even let His hungry disciples pick grain to eat on this holy day. (Matthew 12:1–8; Mark 3:1–6; 7:7)

Some rabbinic sects were more burdensome than others, and their internal divisions caused great conflict in the Jewish judicial system.

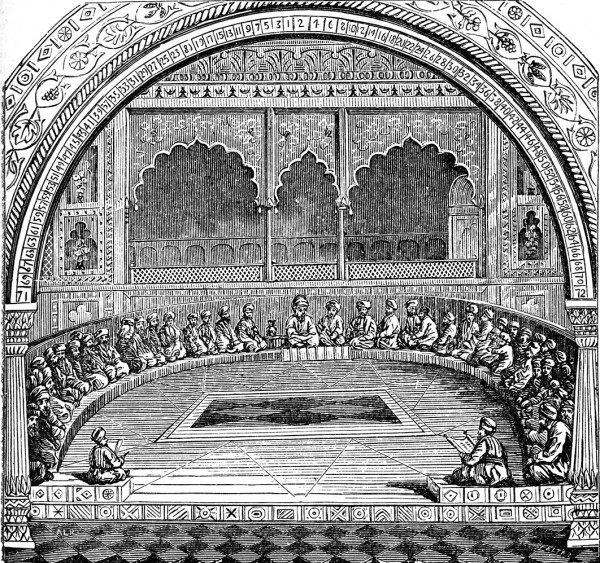

For instance, the Pharisaic sect of Rabbi Shammai (which dominated the High Sanhedrin Court in Yeshua’s day) placed highly restrictive rules upon the people, “binding” them.

The 71-member ancient Jewish Sanhedrin High Court ruled on matters of Jewish law. (Image Source: Wikipedia public domain)

Another leading sect (the Pharisaic disciples of Rabbi Hillel) were much more liberal in their decisions, releasing or “loosening” the people from Shammai’s strict rules and punishments.

As an example, if a man stole a beam and used it to build his house, the school of Shammai taught that the man must tear down his house and restore the beam to the owner, while the school of Hillel taught that the monetary value of the beam must be repaid. (Mishna: Mas. Eduyyot Chapter 7)

Yeshua responded to manmade regulations, especially those of Shammai, by saying, “Woe to you, because you load people down with burdens they can hardly carry, and you yourselves will not lift one finger to help them.” (Luke 11:46)

In contrast to these Rabbinic rules, it had always been God’s desire to bring peace, rest, and freedom to His people, not burdens.

Even as the People of Israel were serving the king of Babylon, God said His desire was “to loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the straps of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke.” (Isaiah 58:6)

How would this freedom happen?

The Yoke of Heaven: The Yoke of Yeshua

By the time Yeshua arrived, the Jewish People were intimately familiar with yokes—yokes of tyrannical Israeli kings, oppressive foreign kings, cruel occupier kings—not to mention back-breaking yokes of rabbinic rules and regulations.

The time had finally come for each of these “yokes of iron” to be cast aside and the light yoke of a holy, righteous King take their place.

Why is Yeshua’s yoke so light?

Certainly, it’s not because following Yeshua is easy. Nor did He promise anyone a rose garden. (Matthew 10:24)

In fact, He promised that whoever tries to preserve his life in this world will lose it, and whoever loses his life in this world will keep it. (Luke 17:33)

A Rabbinic teaching around Yeshua’s time says something similar:

“Rabbi Nechunya ben Hakanah said: ‘Whoever takes upon himself the yoke of Torah, from him will be taken away the yoke of government and the yoke of worldly care; but whoever throws off the yoke of Torah, upon him will be laid the yoke of government and the yoke of worldly care.’” (Pirkei Avot 3:6, written and compiled between 200 BC–AD 200)

By holding on tight to the yoke of the world’s protection and possessions (as Lot’s wife did when she looked back at Sodom), we seek to preserve our lives only in the here and now, which will ultimately lead to our ruin.

But by grabbing hold of the yoke of Yeshua who is the Word of God made flesh, and walking on His path, we seek our heavenly, eternal home with Messiah Yeshua as our King and our eternal hope.

Yeshua’s kingdom on earth began to be demonstrated with His arrival 2,000 years ago. It continues to grow and spread with power as it covers the earth.

To take on the yoke of Yeshua is to take on the yoke of Heaven where righteousness, perfect justice, and peace are the norm because the Sar Shalom (Prince of Peace) reigns as our Lord and Savior, our Messiah Yeshua.

Now that is rest for our souls.

“We fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen. For what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.” (2 Corinthians 4:18)