“Let them praise His name with dancing.” (Psalm 149:3)

Rabbi Shaul (Apostle Paul) exhorts us to “find out what pleases the Lord.” (Ephesians 5:10)

So, what does Scripture tell us about praising God with dance, and how do Jewish People today worship Him with dance?

Let’s find out.

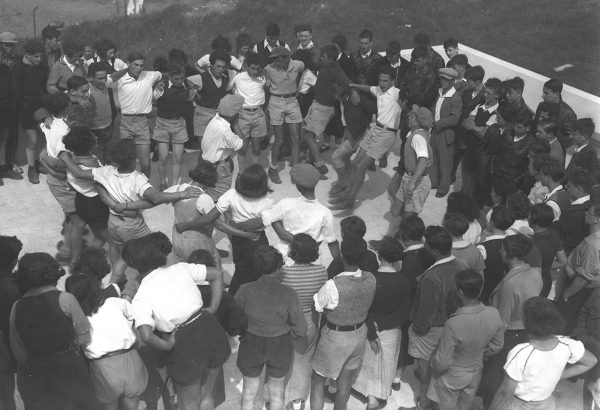

Jewish folk dancing during Shavuot (Pentecost) at Kibbutz Gan—Shmuel.

Dancing with Delight

C.S. Lewis wrote in his book, Reflections on the Psalms that “the most valuable thing the Psalms do for me is to express the same delight in God which made David dance.”

King David famously danced with delight before the Ark of the Covenant as he brought it home to Jerusalem in a procession of musicians and dancing.

The Ark was so holy that anyone who incorrectly touched it was struck dead. Even so, King David, the “man after God’s own heart” decides to dance! (2 Samuel 6:16)

A fresco of King David dancing before the Ark by Johann Baptist Wenzel

It might seem that when David danced before the Ark, he had one of his unwise moments. His wife, Michal, the daughter of Saul, thought so.

“When she saw King David leaping and dancing before the LORD, she despised him in her heart.” (2 Samuel 6:16)

Michal looked at David’s outward display, but God saw his heart as well, how he danced “before the Lord with all his might. (2 Samuel 6:14)

It seems that God was displeased with Michal’s judgment, since we are told Michal had no children after that day.

Michal Despises David, by James Tissot

In the Psalms that he penned, David encourages worshipers to praise the God of Israel just as he did:

“Let Israel rejoice in their Maker; let the people of Zion be glad in their King. Let them praise His name with dancing (machol) and make music to him with timbrel and harp.” (Psalm 149:2–3; 150:4)

After crossing the Red Sea, Moses’ sister Miriam danced (mecholah) with her tambourine to encourage the others to give high praises to the Lord, who had won great victories for His people (Exodus 15:20).

We can also look outside the Bible to learn more about dance in worship:

A Levite is glorifying God by playing a copper pipe or trumpet. On the Temple steps are a lyre, harp, tambourine, cymbals, flute, zither, trigon, psaltery, and symphony.

In Rabbinic literature, we read that at the Temple during the water drawing ceremony on the last day of Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles), the Torah scholars “would dance (rakad) before the people who attended the celebration with flaming torches that they would juggle in their hands, and they would say before them passages of song and praise to God.” (Sukah 51a–b)

At the same time, the Levites would stand on the steps of the Temple and “play on lyres, harps, cymbals, and trumpets, and countless other musical instruments.” (Sukkah 51b)

Dancing in Circles

The Torah scholars at the water drawing ceremony did a rakad (רָקַד) kind of dance, which in Hebrew means to skip, frolic or leap. Safe to say, they were not shy expressing their joy before the Lord.

David and Miriam danced in terms of machol (מָחוֹל) and mecholah (מְחֹלָ). The root of these Hebrew words is the verb chul (חוּל), which means to dance or whirl.

The Bible doesn’t tell us what their dancing looked like exactly, but early Jewish literature presented the machol as a circle dance.

The Gemara (compiled 200–600 AD) says that “in the future, God will make a circle (machol) and will sit among them. Each individual will point with his finger and say, ‘Behold, this is our God for whom we have waited, that he may save us; this is the God for whom we have waited, we will be glad and rejoice in His salvation’ (Isaiah 25:9).” (Ta’anis 31a)

Jewish readers understand machol in this passage to mean a circle dance.

Why a circle?

The 16th century Jewish sage known as the Maharal of Prague explains that in a circle every person faces God, who is in the center, equally and divinely connecting to Him from all sides.

Every leap and jump represents the spiritual heights and holiness that the righteous will experience in the world to come (olam ha—ba), which is not attainable within our finite bodies today, though we can experience it to a small degree with dance.

This is one reason why Jewish dance is often circular.

At all Jewish simchas (festive occasions) such as weddings, bar or bat mitzvahs, and many of the Jewish holidays, you will see Jews cheerfully dancing in circles with arms tightly locked as brothers, leaping with delight.

“In the circle, I dissolves into we,” writes Hasidic Rabbi Tzvi Freeman. “In the circle, there is no cause, no reason, no enemy and nowhere we are going. We are just one. Because we are.”

Jewish men sing and dance at the Western (Wailing) Wall in Jerusalem. (YouTube capture)

Believers in Messiah Yeshua (Jesus) also find a special fellowship in dance during the worship portion of their services.

It’s the sort of oneness we read about in the early chapters of Acts when the disciples, men and women, came together as one for prayer, meals, worship, and fellowship (Acts 1:14, 2:1, 44, 46, 4:24, 5:12).

Davidic dancing (as it is often called among Messianic Believers) bonds one Believer to another and all to God in a special kind of unity.

As we lift our hands and dance to the popular Hebrew song, “Moshiach” (Messiah), our dance is also a prayer, inviting Messiah Yeshua to be there with us, at the center of the circle, so to speak, for He says,

“Where two or three agree, I am there with you.” (Matthew 18:20)

Messianic congregation dances to “Moshiach” (Messiah) . (YouTube capture)

Making of the Legendary Hora

You simply cannot have a Jewish wedding without the festive circle dance that has come to be known as the horah (הורה).

The Hebrew word horah derives from the Greek choros, meaning dance. Some say the original meaning of choros may have been circle.

A new kind of horah entered Israeli culture in 1924 at a time when thousands of young Jewish pioneers were immigrating from around the world to work the land and make it bloom again.

Children from the German “Youth Aliyah” rescue organization, (youth rescued from the Nazi regime) dance the horah at Kibbutz Ein Harod in the Jezreel Valley in 1936.

While touring the pioneer settlements of the Jezreel Valley, the Ohel Workers’ Theatre performed Jewish stories and danced the Agadati horah.

Israeli cultural icon Baruch Agadati (1895 1976) is here performing a Hasidic dance.

This horah (circle dance) presented a revised version of the Romanian horah, choreographed by the Russian—born, classical ballet dancer, painter, and film producer Baruch Agadati.

Six years earlier, in 1918, the song Hava Nagila (Let Us Rejoice!) had already become a hit among the young Zionists.

Hava Nagila was a jubilant song looking for an equally jubilant expression, which it found in Agadati’s hora

Today, at secular weddings, religious bar-mitzvahs, or the beaches of Tel Aviv, dancing the horah to Hava Nagila is an expected site to see.

From Mourning to Dancing

In Psalm 30, the psalmist praises God for hearing his cries for help and says, “You turned my wailing into dancing. … Lord my God, I will praise you forever.” (verses 11–12)

Dancing through sorrow seems to be embedded in the Jewish DNA, even for the nonreligious Jew.

After many Jewish soldiers lost their lives in the Arab Israeli wars, many who remained danced en masse to the melody of Am Yisrael Chai!” (The People of Israel Live!).

Israeli women soldiers dance and sing in Jerusalem. (YouTube capture)

Holocaust survivors have also reported that Jewish people in the death camps tried to do their traditional circle dance, even if they were barely walking.

And in the concentration camps, when Shavuot (Pentecost) came, instead of dancing with Torah scrolls (as is customary), the Jewish men raised rocks on their shoulders to signify the Torah scrolls they no longer had.

When God describes His restoration of the Jewish People into a revived land, He says the “young women will dance and be glad, young men and old as well. I will turn their mourning into gladness; I will give them comfort and joy instead of sorrow.” (Jeremiah 31:13)

Rikudei Am (literally, People’s Dance) are folk dance classes and events (like the one above) held throughout Israel, along the Tel Aviv promenade, at a city square, a community center, or a school. In almost every city, you can find Israeli folk dancing.

The Jewish people have been regathered to their revived homeland, and they now dance as a community in gladness.

But those who praise and honor the Lord as the center of their dance understand His holiness, gladness and joy, the kind that made David dance in delight.