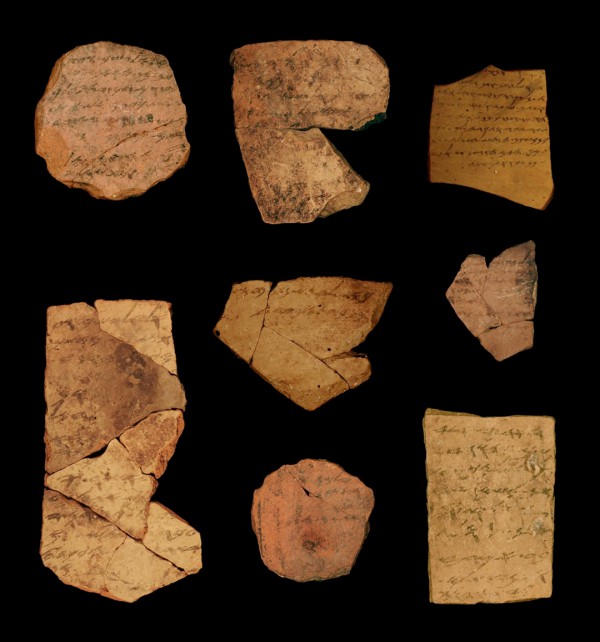

The above ostraca (ink inscriptions on clay) from the fortress of Arad dated to the latest phase of the First Temple Period in Judah, ca. 600 BC, indicating a high literacy level in Judah. Researchers believe that such literacy possibly set the stage for the compilation of Biblical texts. (TAU photo by Michael Cordonsky)

“Then the Lord replied: ‘Write down the revelation and make it plain on tablets so that [whoever reads it] may run with it. For the revelation awaits an appointed time; it speaks of the end and will not prove false.” (Habakkuk 2:2–3)

In the years that Jeremiah and Ezekiel were scribing their prophecies to the Kingdom of Judah (600–580 BC), ancient Israel experienced widespread literacy, according to a handwriting analysis of Hebrew script found on ceramic shards in an isolated desert fort called Arad.

“We found indirect evidence of the existence of an educational infrastructure, which could have enabled the composition of biblical texts,” said Tel Aviv University (TAU) team co-leader and physicist Professor Eliezer Piasetzky.

Sixteen texts, which include information, such as food costs and even instructions for troop movements, but no Scripture, were found together.

Using high-tech digital analysis of the Iron Age script, the Tel Aviv team of archaeologists, math professors, doctoral students in applied mathematics, and one physicist concluded that this ancient collection of Hebrew writings was authored by six or more writers, including the commander of the fort as well as low-ranking soldiers.

Since ancient Arad was only a small garrison far from Jerusalem, inscriptions by multiple authors provide a cross-section of the kingdom that proves broad literacy just before Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of Jerusalem, the team argues.

“Literacy existed at all levels of the administrative, military and priestly systems of Judah. Reading and writing were not limited to a tiny elite,” said Piasetzky. (Arutz 7)

The Muslim Dome of the Rock is thought to sit on the spot where the Jewish First and Second Holy Temples were located.

“Adding what we know about Arad to other forts and administrative localities across ancient Judah, we can estimate that many people could read and write during the last phase of the First Temple period,” added Professor Israel Finkelstein of the TAU Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near East Civilizations, the other team co-leader.

“There’s a heated discussion regarding the timing of the composition of a critical mass of Biblical texts,” Finkelstein added, linking it to the question of literacy rates in the Judean Kingdom and, later on, in exile.

The research results, published last Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, helped to resolve this controversy. It dated the handwritings from Arad to 600 BC — within the lifetime of Jeremiah and Ezekiel, and about 20 years after King Josiah of Judea discovered the Book of the Law in the Temple (2 Kings 22–23).

Therefore, it seems that when the Lord told Ezekiel to “write [the design and laws of the Temple] in their sight, so that they may observe its whole design and all its statutes and do them,” He fully expected the Israelites to read the Word of God that Ezekiel himself wrote. (Ezekiel 43:11)

Thanks to the literacy of ancient Israel, God’s written Word has been passed on from generation to generation for us to learn and obey as well.